Yowao's Stories

Introduction

Yowao in a garden

Yowao Jarawara was born probably in about 1924, in a village near the Igarapé Preto stream,1 in what is now the Jamamadi-Jarawara reservation.2

The name Yowao is Portuguese – João. He also had a name in Jarawara, i.e. Kana Abono, but people normally called him Yowao.

Between 1987, when my wife Lucilia and I were assigned to the Jarawara project by SIL, and Yowao's death in 2002, I recorded many stories told by Yowao, most of which are published here. He was one of the two main story tellers of Casa Nova village, along with his first cousin Siko, whose stories I also published recently. Yowao's story about Saba was one of the very first stories I recorded.

When I published the collection of Siko's stories (Vogel 2022a), almost all the stories had been previously published, in volumes 1 and 2 of the Jarawara texts that I had made available online (Vogel 2012, 2019). Some of Yowao's stories in the present collection were likewise previously published in these two volumes, but most of the stories are previously unpublished.

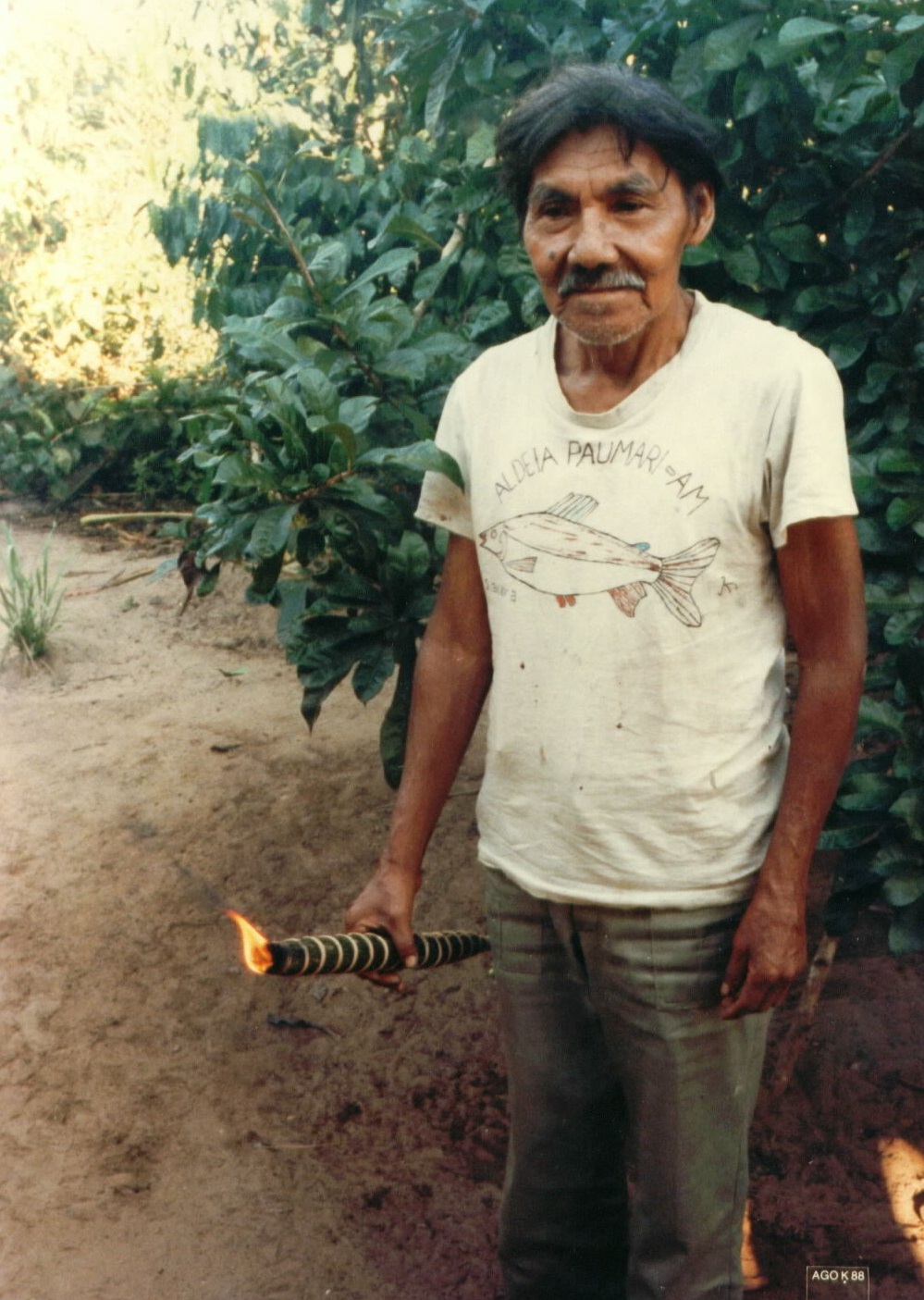

Yowao with a traditional torch

Yowao's name in Jarawara, Kana Abono, means 'spirit of sugar cane'. Yowao was a powerful shaman, and this is reflected in his stories, a good number of which have to do with spirits. Besides being a shaman, Yowao was also a village chief. He and his wife Aobina had thirteen children, and so just about everyone in Casa Nova village is a descendant or married to a descendant.

The texts were originally recorded on cassette tape, and transcribed with the help of a number of literate Jarawaras. Many remaining questions were resolved in sessions with Okomobi and Bibiri, Yowao's son and grandson, respectively, both of whom have a true gift for language. The recordings were made in Casa Nova village. The texts were interlinearized using Fieldworks Language Explorer (FLEx).3 The reader will note that there are two or more versions of some stories in this collection, recorded on different occasions.

I make a practice of getting written permission from Jarawara authors of texts to use the texts for non-commercial purposes, but I did not start doing this until after Yowao was already dead; so for these texts the permissions were signed by relatives of his.

Aobina, Yowao's wife

These texts should not be seen as polished written texts. All of the texts are originally oral texts, none are originally written. The recordings are unedited, and the transcriptions reflect the recordings as exactly as possible. This means, for example, that false starts, repetitions of words, and occasional grammatical mistakes are retained in the transcription. Some of these are discussed in footnotes, but most are not.

The texts are divided into two groups, personal experience narratives and traditional stories. The personal experience stories include both accounts of Yowao's own experiences, and those of others who he knew personally, or at least people he knew his connection to. The traditional stories, in contrast, involve characters in the more distant past. Whereas Siko's stories were mostly traditional stories, Yowao's stories are more balanced between personal experience narratives and traditional stories.

The following format is used for each text. First a free translation is given of the text, and this is followed by the text in interlinear format. The first line of the interlinear format is orthographic. The second line represents underlying forms4 and morphemic divisions, the third line morpheme-by-morpheme glosses, the fourth line word classes, and the last line a sentence by sentence translation. The sentence by sentence translation is as literal as possible, in contrast to the free translation at the beginning of each text, which seeks to express the meaning of the text in more natural English. In the free translation, some implied information is added, participant reference (e.g. choice of a pronoun or an NP) follows the conventions of English, and some repetition is omitted.

Note that some Jarawara sentences are very long, because of the way many "dependent clauses" are sometimes strung together. For more information on dependent clauses, see Dixon (2004) and Vogel (2009, 2022b).

The Jarawara orthography is pretty much phonemic and transparent, except that long vowels are not distinguished. For an explanation of the orthography, see my Jarawara-English Dictionary (Vogel 2016), which is online. In the line for underlying forms, the symbol I is used to represent a morphophoneme that is realized as i or e, depending on the number of moras preceding in the word, i if the preceding number of moras is even and e if the preceding number of moras is odd (cf. Dixon (2004:40ff)).

In the orthographic line I have used punctuation in the normal ways, with one significant exception. Whereas the normal use of commas is to indicate grammatical pauses, I have used commas to indicate phonetic pauses. Some readers may find this awkward, since the pauses are often in the middle of a phrase and are not for any grammatical reason – speakers often pause just to think of what to say next – but I wanted to register this information, and could not think of any other way to do it.

The following abbreviations are used:

1 - first person

FP - far past

O - direct object

1EX - first person plural exclusive

F.PL - plural and feminine

OC - O-construction

1IN - first person plural inclusive

fpropn - feminine proper noun

PFUT - past in future

2 - second person

FUT - future

PL - plural (i.e. two or more)

3 - third person

HAB - habitual

pn - inalienably possessed noun

adj - adjective

HYPOTH - hypothetical

POSS - possessor/possessive

ADJU - adjunct

IMMED - immediate

post - postposition

adv - adverb

IMP - imperative

pron - pronominal

antip - antipassive

INT - intentive

prt - particle

AUX - auxiliary

interj - interjection

RECIP - reciprocal

BKG - backgrounding

interrog - interrogative pro-form

REFL - reflexive

CAUS - causative

IP - immediate past

REP - reported

CH - change of state

IRR - irrealis

result - resultative

COMPL - complement

LIST - list construction

RP - recent past

COMIT - comitative

LOC - locative

S - subject

conj - conjunction

+M - masculine agreement

SEC - secondary verb

CONT - continuative

mpropn - masculine proper noun

SG - singular

CNTRFACT - contrafactual

N - non-eyewitness evidentiality

sp - species

CQ - content question

NEG - negative

sound - sound word

DECL - declarative

NEG.LIST -tnegative list item

SUPER - superlative

DEM - demonstrative

nf - feminine noun

vc - copular verb

DIST - distal

NFIN - non-finite

vd - ditransitive verb

DISTR - distributive

nm - masculine noun

vi - intransitive verb

DUP - reduplication

NOM - nominalized clause

voc - vocative

E - eyewitness evidentiality

NPQ - noun phrase question

vt - transitive verb

+F - feminine agreement

Those wishing more information on the syntax, morphology, and phonology of Jarawara may consult R.M.W. Dixon’s (2004) grammar, The Jarawara Language of Southern Amazonia, and the introduction to my Jarawara-English Dictionary.

I welcome any comments or questions, and I can be reached at [email protected].

Footnotes

1 For a map of present and former Jarawara villages, see Maizza (2009:192).

2 Almost all the approximately 230 speakers of Jarawara live on this reservation, which is in the municipality of Lábrea in the state of Amazonas, Brazil.

3 FLEx is available for free download from the SIL International site (sil.org).

4 The second line is intended to represent underlying phonological forms, including long vowels, which are not represented in the Jarawara orthography. However, in some cases the underlying form is more morphological than it is phonological. There are vowel alternations of Jarawara verbs that are reflexes of grammatical processes, namely gender agreement and the derivation of non-finite forms. Where an underlying morphological form can be determined, I use it instead of all the forms that result from grammatical processes. For example, the suffix -ma 'back' typically has only this one form in contexts where there is no gender agreement, and typically has a -ma/-me alternation in other contexts to show feminine and masculine agreement, respectively. I use -ma as the underlying form in all contexts, but show gender agreement on the second line ('-back+F' or '-back+M') in all contexts where the form indicates the normal gender agreement found in finite clauses.

Similarly, a non-finite form is derived by changing a final a to i, but I use the form with a as the underlying form even when it is a non-finite form, and I indicate that the form is non-finite by adding NFIN. For example, I give the underlying form of fawa 'to drink', which is fawi, as fawa.NFIN. One of the advantages of doing things this way is that a search for all the tokens of a particular morpheme is made much easier. Also, this way it is possible to indicate that a form is non-finite even if there is no a to i change, which is the case for verbs ending with o, i, or e.

In Jarawara there is a construction called a "list construction", and one of the exponents of this construction is the obligatory absence of gender agreement in the verb stem. Whenever this is the case, I indicate this on the second line. For example, when fawa is in a list construction, this is indicated on the second line as fawa.LIST. This way, the reader knows the reason that a at the end of the verb does not indicate feminine agreement. (Since the items in a list construction can sometimes be NPs, the same notation is used to mark these.)

There is one more construction that is marked on the second line, i.e. nominalized clauses. These verb forms are marked with NOM, along with the gender when this is indicated in the form, i.e. NOM+F or NOM+M. This gender agreement is thus distinguished from the normal gender agreement of finite clauses.

References

Dixon, R.M.W. 2004. The Jarawara language of Southern Amazonia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Maizza, Fabiana. 2009. Cosmografia de um mundo perigoso: espaço e relações de afinidade entre os Jarawara da Amazônia. PhD disseertation, Universidade de São Paulo.

Vogel, Alan. 2009. Covert tense in Jarawara. Linguistic Discovery 7:43-105. http://journals.dartmouth.edu/cgi-bin/WebObjects/Journals.woa/xmlpage/1/article/333.

Vogel, Alan. 2012. Jarawara interlinear texts vol. 1. http://www.silbrazil.org/resources/jarawara_interlinear_texts_vol_1.

Vogel, Alan. 2016. Jarawara-English dictionary. http://www.silbrazil.org/resources/archives/72031.

Vogel, Alan. 2019. Jarawara interlinear texts, vol. 2. https://www.silbrazil.org/resources/jarawara_interlinear_texts_vol_2.

Vogel, Alan. 2022a. Siko's stories. https://www.silbrazil.org/resources/sikos-stories.

Vogel, Alan. 2022b. A typology of finite subordinate clauses in Jarawara. Cadernos de Etnolingüística, Série Monografias, 6. http://www.etnolinguistica.org/mono:6.

List of Texts

Part I: Personal Experience Narratives

audio (9m 23s)

1991

audio (3m 41s)

1991

audio (1m 03s)

1991

audio (29m 58s)

1992

audio (7m 48s)

1992

audio (5m 03s)

1992

audio (14m 06s)

1992

audio (23m 49s)

1992

audio (9m 17s)

1992

audio (13m 35s)

1992

audio (20m 53s)

1992

audio (13m 49s)

1992

audio (34m 24s)

1992

audio (8m 13s)

1992

audio (48m 06s)

1992

audio (5m 41s)

1992

audio (14m 24s)

1993

audio (32m 06s)

1993

audio (1h 12m 58s)

1993

audio (9m 54s)

1993

audio (24m 07s)

1993

audio (12m 28s)

1994

audio (30m 03s)

1994

audio (12m 38s)

1994

audio (11m 37s)

1994

audio (8m 22s)

1994

audio (12m 52s)

1994

audio (13m 50s)

1994

audio (10m 38s)

1994

audio (16m 18s)

1994

audio (7m 11s)

1994

audio (10m 55s)

1997

Part II: Traditional Stories

audio (4m 25s)

1987

audio (11m 00s)

1991

audio (2m 57s)

1991

audio (8m 47s)

1991

audio (4m 46s)

1991

audio (45s)

1991

audio (2m 55s)

1991

audio (2m 17s)

1991

audio (13m 54s)

1991

audio (8m 03s)

1991

audio (5m 10s)

1991

audio (7m 57s)

1991

audio (1m 32s)

1991

audio (18m 40s)

1992

audio (5m 23s)

1992

audio (4m 02s)

1992

audio (20m 10s)

1992

audio (30m 18s)

1992

audio (44m 31s)

1992

audio (13m 00s)

1992

audio (5m 39s)

1992

audio (5m 55s)

1992

audio (10m 42s)

1992

audio (15m 52s)

1992

audio (7m 53s)

1992

audio (11m 22s)

1992

audio (17m 12s)

1992

audio (6m 10s)

1993

audio (8m 18s)

1993

audio (34m 10s)

1993

audio (22m 03s)

1993

audio (7m 07s)

1993

audio (9m 23s)

1993

audio (15m 51s)

1993

audio (19m 59s)

1993

audio (36m 35s)

1993

audio (10m 12s)

1994

audio (7m 35s)

1994

audio (5m 16s)

1994

audio (9m 15s)

1994

audio (15m 29s)

1994

audio (2m 43s)

1994

All of the Texts in a Single PDF File

Jarawara Interlinear Texts 1 Jarawara Interlinear Texts 2 Siko's Stories Return to Brazil Resources